Mexico’s Ghost Towns

The other side of the immigration debate

By John Gibler (ZACATECAS, Mexico )

Cerrito del Agua, population 3,000, has no paved roads — either leading to it or within it. No restaurants, no movie theaters, no shopping malls. In fact, the small town located in the central Mexican state of Zacatecas has no middle schools, high schools or colleges; no cell phone service, no hospital. Its surrounding fields are dry and untended. The streets are empty.

The explosion of emigration to the United States over the past 15 years has emptied much of central Mexico, even reaching into southernmost states like Chiapas and Yucatan. But it has simply devastated Zacatecas, a dry, rolling agricultural region located about 400 miles northwest of Mexico City.

A little more than half of Zacatecas’ population — about 1.8 million people — now live in the United States, especially in areas surrounding Atlanta, Chicago and Los Angeles. Between 2000 and 2005, three out of its four municipalities registered a negative population growth. A 2004 state law created two new state legislative posts for migrants living in the United States. In 2006, depopulation cost the state one of its five congressional districts.

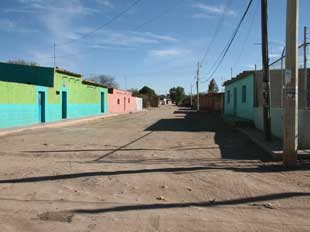

In Mexico's Cerrito del Agua, freshly painted concrete

houses line empty streets because most of their owners

are working in the United States.

“Well, you’ve seen what this place is like,” says Dr. Manuel Valadez Lopez, gesturing out the door of his small private clinic when I ask him how emigration has affected the town. “There has not been even minimal development here. There is not a single yard of pavement. The few people who have sidewalks in front of their houses built them themselves. Most people defecate outdoors.”

Lopez, 40, a native of Cerrito del Agua, is one of the few to leave the town and return. All six of his brothers now live and work in the United States. All four of his sisters married men who left to work in the United States.

In his teens, Lopez himself had moved to Guadalajara (about a five-hour drive southwest of Zacatecas) to attend high school and university, then stayed on to study medicine and receive a specialist’s training in gynecology. He later returned to Cerrito del Agua for a visit and realized “there was so much work to do here that I stayed,” he says.

That was eight years ago.

“The whole culture now is that people grow up and go to the U.S. — their parents, their uncles, their brothers and sisters, everyone goes,” Lopez says. “The kids who are strong and smart, they all go to the U.S. There are no basic services here; the government has not carried out a single project.”

The situation has been so dire, he says, that the staff at the clinic had to install its own sewage system. “There is running water, but it’s not clean,” he continues. “People get all sorts of infections, a typical Third-World situation.”

Worst of all, says Lopez, is that “people who could possibly stay here and do something, they all go.”

The new U.S. colony

A January report by Richard Nadler, president of the conservative Americas Majority Foundation, found that the strongest state economies in the United States are those with high numbers of migrant workers. Nadler writes: “An analysis of data from 50 states and the District of Columbia demonstrates that a high resident population and/or inflow of immigrants is associated with elevated levels and growth in gross state product, personal income, per capita personal income, disposable income, per capita disposable income, median household income and median per capita income.”

Those who are leaving Mexico — those whose land goes unplanted, whose roads remain unpaved — are laboring in the United States, building shopping malls and factories, washing dishes in restaurants and cafés, picking grapes and pulling lettuce.

They are creating within the U.S. economy precisely the goods and services that their hometowns lack. At the same time, their anemic home economies falter on the brink of collapse.

“I think that the U.S.’s plan is to make Mexico into a kind of colony,” says Lopez, with a half smile. “People go to the U.S. to work and earn dollars. They come back to Mexico and spend their dollars on American products. It’s a nice, round business.” He continues: “Everyone here depends on the U.S. If this isn’t a colony, then how do you define colony?”

Condemned to disappear

In the heated debates over U.S. immigration policy, the pressing questions seem to be “How many immigrants should be allowed in, if any?” and “How should they be processed into the system?” But rarely considered is what this massive influx is doing to Mexico.

With nearly half a million Mexicans crossing the U.S.-Mexico border every year to look for work, Mexico has become the world’s largest exporter of its people. More people flee destitution in Mexico than in China or India — each with populations 10 times larger than Mexico’s.

Their remittances — the money Mexican immigrants in the United States save and send back to their families — equaled $24 billion last year, and made up the third-largest source of revenue for the Mexican economy (after illegal drugs and oil).

“Theories of migration always show the interests of the North,” says Raul Delgado Wise, director of the Graduate School of Development Studies at the Autonomous University of Zacatecas and an expert on migration. He says migrants born in Mexico contribute 8 percent of the U.S. gross domestic product (GDP) — about $900 billion — which is more than Mexico’s entire GDP.

Wise is one of several researchers studying Mexican migration at the University of Zacatecas. Together they publish an international journal called Migration and Development and are laying the groundwork for an alternative think tank to the World Bank, which will be called the Consortium for Critical Development Studies.

“With all of this, we need to see really how much it is costing Mexico, how much Mexico is losing,” Wise says.

He says that the mass migration from Mexico to the United States cannot be fully understood without considering the U.S.-Mexico economic integration. Begun in the ’80s, this integration reached its maximum expression with the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), which took effect Jan. 1, 1994.

What Mexico really exports, Wise argues, is labor.

The supposed growth in Mexico’s manufacturing sector is a “smokescreen,” he wrote in a 2005 article in Latin American Perspectives, a scholarly journal. Almost half of all manufacturing exports come from the maquiladora assembly plants (foreign-owned factories in Mexico) that import production materials and export their final products — and their profits. Mexico adds only the labor.

Neoliberal policies — first implemented in the ’80s, and later through NAFTA — cut government investment in public works and agriculture, privatized key state enterprises and created low interest rates that attracted foreign capital. These policies opened the way for a 25-fold increase in maquiladora sales between 1982 and 2003 (though that growth peaked in 2000 and has since fallen as maquiladora owners seek ever lower wages and looser environmental regulations to compete with China’s abundant labor supply).

From 1994 to 2002, Mexico lost more than 1 million agricultural jobs. And from 1980 to 2002 — the same period maquiladora sales soared — migration from Mexico to the United States grew by 452 percent, with more than 400,000 people crossing each year, on average.

“In Mexico, we have exported the factory of migrants,” says Rodolfo Garcia Zamora, an economics professor who also teaches at the Graduate School of Development Studies. Zamora, author of Migration, Remittances and Local Development, says Mexico “is mortgaging its future” with migration and remittances. In the 10 Mexican states with the longest migration histories, he says, 65 percent of municipalities have a negative population growth. “This means that in the future,” says Zamora, “these communities will not be able to reproduce, neither economically nor socially, because the demographics of migration have condemned them to disappear.”

No escape?

“The United States economy demands cheap labor. Mexico has an excess of laborers. We complement each other,” says Fernando Robledo, director of the Zacatecas State Migration Institute, a government office that administers development projects in conjunction with several U.S. migrant organizations.

He dismisses talk of depopulation and an abandoned countryside as “fatalism.” “Zacatecas has a 120-year history of migration,” he says. “Migration is historical.”

Robledo describes the state government’s development priorities as variations on the “three for one” program — where local, state and federal governments match each dollar provided by U.S. migrant organizations for use in local development projects, such as building interstate highways heading north and constructing greenhouses for growing export crops.

“If you had $50 million in the budget,” Robledo says, “would you use that to increase production in the countryside or to build an interstate highway? It is a political and economic decision.”

Robledo puts priority on the highway.

But doesn’t building super-highways toward the Mexico-U.S. border and changing agriculture to a cash-crop export reproduce the very neoliberal policies that dispossess migrants in the first place?

“We do not live in a socialist country,” he responds, “where the government controls every aspect of the economy. We are in a neoliberal country. We cannot escape from neoliberal economics.”

Garcia Zamora, who helped write the Zacatecas state development plan, is unconvinced. The main problem, he says, is the lack of real political alternatives to neoliberalism. According to Zamora, “there is only one political party in Mexico — the PRI,” referring to Mexico’s notoriously corrupt Institutional Revolutionary Party, which ruled the country from 1929 to 2000. “The PRD government in Zacatecas now acts just like a PRI government,” Zamora says, this time referencing the Party of the Democratic Revolution, the opposition party to the PRI. “The same lack of planning and nepotism. It spends its time mainly implementing federal programs. They drafted a good development plan, but they … have never carried out a serious regional economic development policy that seeks to diminish the massive exodus of 40,000 Zacatecas residents who abandon Mexico every year.”

Abandoned by migration

A few years ago, Mario Garc’a left Zacatecas to work in construction in Southern California, but after about five months he decided to return to El Cargadero, a tiny town about 50 miles west of the city of Zacatecas, the state capital.

“I thought, ‘In Mexico, if you work a couple of shifts, you can live OK’, ” he says. “Without so many luxuries and freeways, but you can live a more peaceful life.”

Garc’a, in his early 40s, is a small farmer and municipal delegate. His wife and three daughters live in El Cargadero. All nine of his brothers and sisters, and more than 50 cousins, live in the United States.

El Cargadero, with a population of about 350, and a population in the United States of more than 1,000, is supposed to be a success story. Most of its roads are freshly paved, and residents have electricity and potable water, thanks to remittances and the “three for one” program.

“There are many points of view, but as you can see here, this is a community abandoned by migration,” Garc’a says. “The government should work to keep people in the country, to find jobs, better living conditions. Here we have pretty streets, but where are the people?”

Driving from the city of Zacatecas to El Cargadero, mile after mile of empty fields, closed restaurants and boarded-up houses span the countryside. José Manuel, a taxi driver, who worked in California for four years, washing dishes and making salads, accompanies me on the drive. He says he remembers when these roads weren’t paved yet, but the fields were full of corn and beans. It is now vast emptiness.

“Nobody works most of this land anymore,” he says. “The owners went to the U.S. and left the land behind.”

This is precisely what brought Mario Garc’a back. “The countryside is broken,” he says. “The rural economy needs to be reactivated. But we export one of the most valuable things: our workers. And now we don’t produce anything.”

The legalization debate is misguided, he says, because it focuses, always, on the U.S. economy: how many immigrants to allow in and how to stamp their passports. That focus needs to shift to include Mexico.

“Mexico does not need an open border with the U.S. that invites Mexicans to go work there. People always talk about legalization, but no, what needs to be legalized is the Mexican’s ability to stay [home] so that Mexico can grow and produce.”

John Gibler is a Global Exchange Media fellow who writes from Mexico. He is the author of Mexico Unconquered: Chronicles of Power and Revolt, forthcoming from City Lights.